Japanese Flower Arrangement: The Art of Ikebana and Its Timeless Principles

Introduction

Japanese flower arrangement represents one of the most refined artistic traditions to emerge from Japan, with roots extending back over 600 years to the temples and aristocratic homes of Kyoto. The origins of ikebana can be traced back to the ancient Japanese custom of erecting evergreen trees and decorating them with flowers to invite the gods, highlighting its deep cultural and spiritual significance. This disciplined art form, known as ikebana, transforms the simple act of arranging flowers and plants into a meditative practice that connects practitioners with nature, seasons, and deeper philosophical truths, all while honouring a rich tradition passed down through generations.

This guide covers the complete landscape of ikebana flower arrangement—from its Buddhist origins and philosophical foundations to practical techniques modern florists can apply immediately. Whether you are a professional floral artist seeking to expand your creative repertoire, a flower enthusiast drawn to Japanese aesthetics, or someone exploring mindfulness through creative practice, this content addresses your specific needs while remaining accessible to beginners. In ikebana, every arrangement is an opportunity to be present, capturing the spirit of the moment and finding serenity in the fleeting beauty of each creation.

Japanese flower arrangement, known as ikebana, is a disciplined art form that emphasises harmony, balance, and the spiritual connection between humanity and nature, distinguishing itself from Western approaches by prioritising negative space, line, and form over mere abundance.

By engaging with this material, you will:

-

Understand the core principles that define authentic ikebana arrangements

-

Recognise and differentiate between classic ikebana styles

-

Appreciate the philosophical and spiritual foundations underlying this Japanese art

-

Learn fundamental techniques for creating balanced compositions

-

Apply these timeless concepts to enhance modern flower arranging practice

History of Ikebana

You know that feeling when you walk into a room and something just feels... right? That's what happens when you encounter ikebana for the first time. This isn't just flower arranging — it's something that reaches back more than six centuries, carrying with it the whispered prayers of Buddhist monks and the quiet wisdom of countless hands that understood something we're still learning: that beauty and spirit aren't separate things. When Buddhism made its journey from China and Korea to Japan in the 6th century, it brought with it more than teachings. Those early priests, homesick perhaps for the sacred spaces they'd left behind, began creating simple flower offerings called kuge — not because they had to, but because something in their hearts needed to honor Buddha this way. Picture those first arrangements gracing the tokonoma, that special alcove in Japanese homes where only the most treasured things belong. These weren't decorations — they were conversations between human hands and the divine, each stem placed with the kind of intention that changes everything.

There's something magical about watching an art form find its voice, and that's exactly what happened during the Muromachi period from 1336 to 1573. Those same Buddhist priests, the ones who spent their days listening to the rhythm of seasons changing, began crafting arrangements that weren't just beautiful — they were alive with meaning. Every branch whispered secrets about interconnectedness, every leaf told stories about the seasons, and if you knew how to read the language they were creating, those arrangements could break your heart or lift your spirit. They weren't just decorating sacred spaces anymore; they were creating a vocabulary of emotion using nothing but flowers, branches, and an understanding of how nature speaks when we're quiet enough to listen.

By the 16th century, something extraordinary was happening — ikebana was splitting into styles that would define its future forever. The Rikka style emerged like a formal prayer, structured and reverent, creating these miniature landscapes that somehow contained the grandeur of entire mountains and valleys in a single arrangement. You could stare at a Rikka arrangement and feel like you were looking at the whole world. Then came Nageire, born in the intimate setting of tea ceremonies, and this style was different — it whispered where Rikka proclaimed, embracing a kind of effortless grace that looked like the flowers had simply chosen to arrange themselves that way. The tea ceremony itself became this perfect stage where a single, perfectly placed flower could steal your breath and remind you that sometimes the most profound truths live in the simplest gestures.

The Edo period — 1603 to 1867 — was when ikebana truly came alive and started dancing. Schools began sprouting like spring flowers after rain, each one developing its own voice, its own secrets, its own way of making beauty from chaos. The Ikenobo school, already established since the 15th century, became the keeper of both Rikka and Shoka styles, setting standards that still make modern practitioners pause in reverence. But then came innovators like the Ohara school, pioneering the moribana style that changed everything, and Sogetsu, which threw open the doors and said "create freely" — suddenly ikebana wasn't just for temples and aristocrats anymore. It was flowing into everyday homes, into the hands of ordinary people who discovered they could create extraordinary beauty with nothing but flowers and intention.

Here's what makes ikebana different from anything else you'll ever encounter — it understands that empty space isn't nothing, it's everything. Those practitioners, century after century, have been masters of the pause, the breath, the moment between moments where meaning lives. They celebrate the materials that nature offers — not fighting against the curve of a branch or the way a flower naturally wants to lean, but working with these gifts to create harmony that you can feel in your bones. Whether someone creates a simple arrangement that takes five minutes or spends hours crafting something elaborate, what they're really doing is capturing time — those fleeting moments when beauty and impermanence meet and create something that touches your soul long after the flowers have faded.

Walk into any ikebana studio today — whether it's tucked away in a traditional Japanese home or thriving in a contemporary space on the other side of the world — and you'll feel it immediately. This isn't just an art that survived; it's one that's still growing, still breathing, still teaching us how to see. Students gather around masters who carry forward techniques that were perfected centuries ago, yet they're also bold enough to embrace new materials, fresh interpretations, ways of honoring tradition while making it speak to our modern hearts. Alongside the tea ceremony and incense appreciation, ikebana remains one of those rare gifts — an art that doesn't just create beauty, but transforms the person creating it, reminding us that in a world moving too fast, there's still magic in slowing down enough to arrange flowers with the same reverence those first Buddhist priests brought to their simple offerings all those centuries ago.

Understanding Japanese Flower Arrangement Fundamentals

Ikebana—literally meaning “arranging flowers” or “making flowers alive”—transcends simply putting flowers in a vase. This art of flower arrangement treats each stem, branch, and bloom as an element in a living sculpture, where the spaces between materials carry equal importance to the materials themselves. Master teachers and schools teach the principles and philosophy of ikebana, passing down techniques and traditions through generations to preserve and advance this refined discipline. For florists and enthusiasts accustomed to Western approaches, ikebana offers a transformative perspective on what flower arrangement can achieve.

The practice of ikebana evolved from simple flower offerings at Buddhist altars to more elaborate and artistic arrangements over centuries, particularly influenced by Buddhism. This evolution shaped the unique aesthetics and spiritual depth that define Japanese flower arrangement today.

Core Philosophy and Principles

Seven fundamental principles guide authentic Japanese flower arranging: Silence, Minimalism, Shape and Line, Form, Humanity, Aesthetics, and Structure. These interconnected concepts create arrangements that convey meaning beyond visual beauty, expressing the arranger’s understanding of nature and life itself.

Central to ikebana is the concept of negative space, known as ma in Japanese. Unlike Western arrangements that often fill every visual gap, ikebana arrangements deliberately incorporate emptiness as a design element. This negative space allows the eye to rest, creates visual rhythm, and suggests the expansiveness of nature within a contained composition.

Understanding these principles enhances any floral design, regardless of style. A florist who grasps ma creates more sophisticated Western arrangements; an enthusiast who appreciates minimalism develops a keener eye for selecting materials.

Cultural and Spiritual Significance

The origins of ikebana intertwine with both Buddhism and Shinto traditions. When Buddhism arrived from China during the Asuka Period (6th century), Buddhist priests began placing floral offerings on temple altars—arrangements that evolved from simple devotional acts into structured artistic practice. Simultaneously, Shinto customs of erecting yorishiro (objects to summon divine spirits) contributed reverence for natural materials.

In Japanese culture, flowers carry different meanings that shift with seasons. Cherry blossoms evoke transience; chrysanthemums represent longevity; pine suggests endurance. This symbolic vocabulary, called hanakotoba, enables arrangements to convey messages without words, connecting ikebana to broader Japanese aesthetics of subtlety and suggestion.

Ikebana also shares deep connections with other classical Japanese arts, particularly the tea ceremony and incense appreciation. These three classical Japanese arts developed together in Kyoto’s temples and aristocratic circles, each emphasising mindfulness, seasonal awareness, and finding beauty in simplicity. The tokonoma alcove in traditional Japanese homes often displayed ikebana arrangements alongside calligraphy and incense, creating a unified aesthetic experience.

This philosophical foundation directly shapes the practical styles that emerged across centuries of practice.

Traditional Ikebana Styles and Schools

From these spiritual and aesthetic foundations, various schools and styles developed, each interpreting ikebana’s core principles through distinct approaches. In fact, there are millions of different schools of Ikebana in Japan, each with its own unique techniques, styles, philosophies, and grandmasters. Today, over 3,000 schools exist in Japan, though three major lineages—Ikenobo, Ohara, and Sogetsu—dominate practice worldwide, each teaching different methods while honouring shared principles. According to Shozo Sato, a renowned authority and author on ikebana, the historical development of these schools reflects the art’s rich diversity. Rikka and Nageire are the two main branches into which Ikebana has been divided, each offering distinct philosophies and styles.

Rikka Style

Rikka, meaning “standing flowers,” emerged during the Muromachi period as the first codified ikebana style. This elaborate approach creates symbolic landscape representations within the arrangement, with each of nine key positions representing elements of nature—from mountain peaks to flowing water.

The classic styles of rikka reached their zenith during the Azuchi-Momoyama Period (late 16th century), when unification under Hideyoshi Toyotomi led to grand castle tokonoma alcoves demanding massive displays. Senko Ikenobo I created arrangements praised as “the greatest Ikenobo work of an age” for noble celebrations.

Modern applications of rikka suit formal venues, cultural exhibitions, and spaces requiring dramatic impact. While challenging for beginners, studying rikka teaches fundamental principles of balance, proportion, and symbolic arrangement that inform all other styles.

Nageire Style

The nageire style—literally “thrown in”—emerged from Zen Buddhism’s influence, emphasising spontaneous beauty over rigid formality. Unlike rikka’s precise positioning, nageire arrangements appear naturally placed, as if flowers fell gracefully into tall vases without deliberate arrangement.

This deceptive simplicity requires deep understanding of natural materials and how branches and stems behave. The style highlights ikebana’s meditative quality: the arranger must quiet the mind, observe the material’s inherent nature, and respond intuitively rather than imposing predetermined designs.

Nageire represents a significant evolution from formal styles, demonstrating how Japanese ikebana adapted to different philosophical influences while maintaining core principles of harmony with nature.

Seika and Moribana Styles

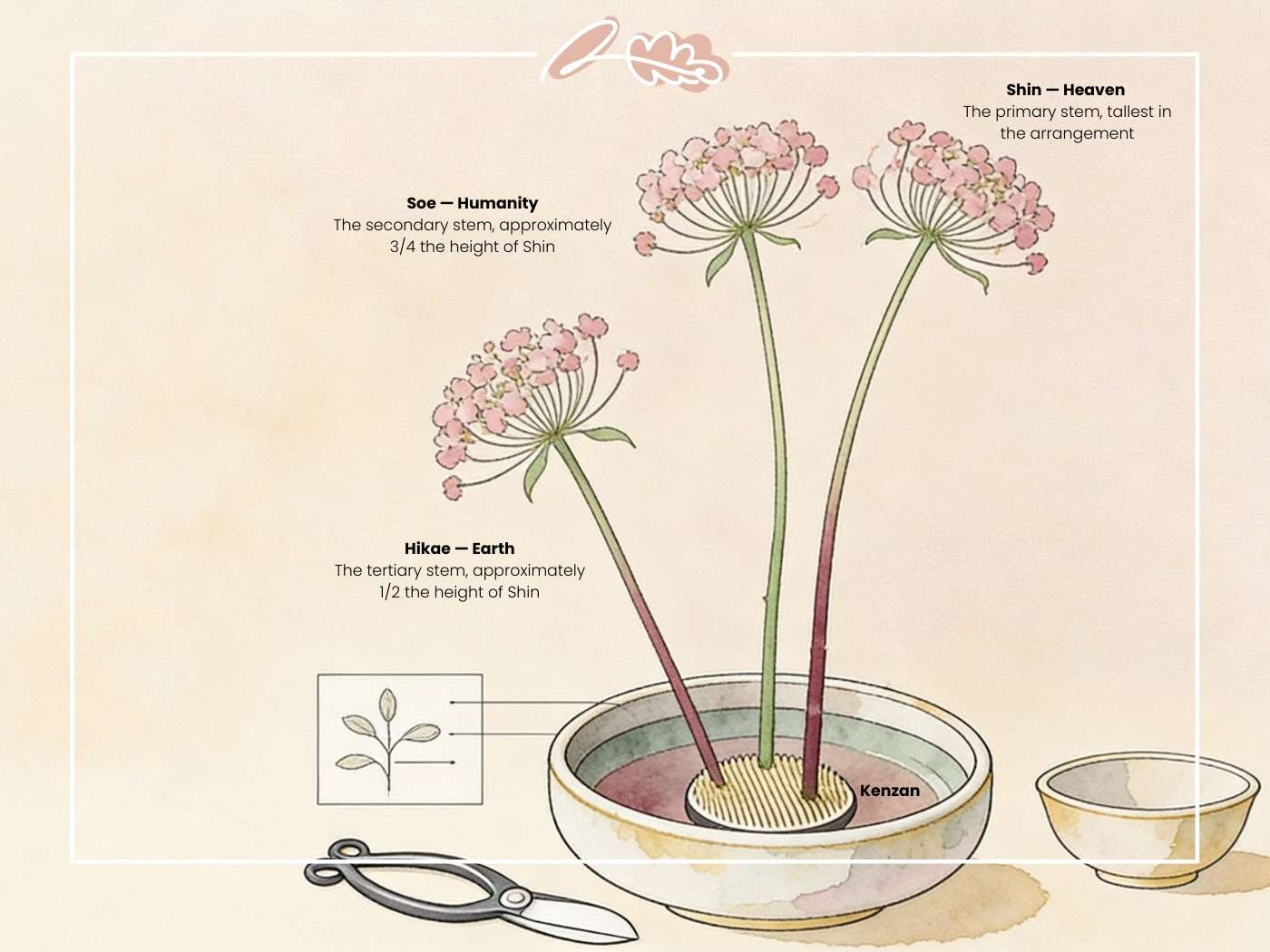

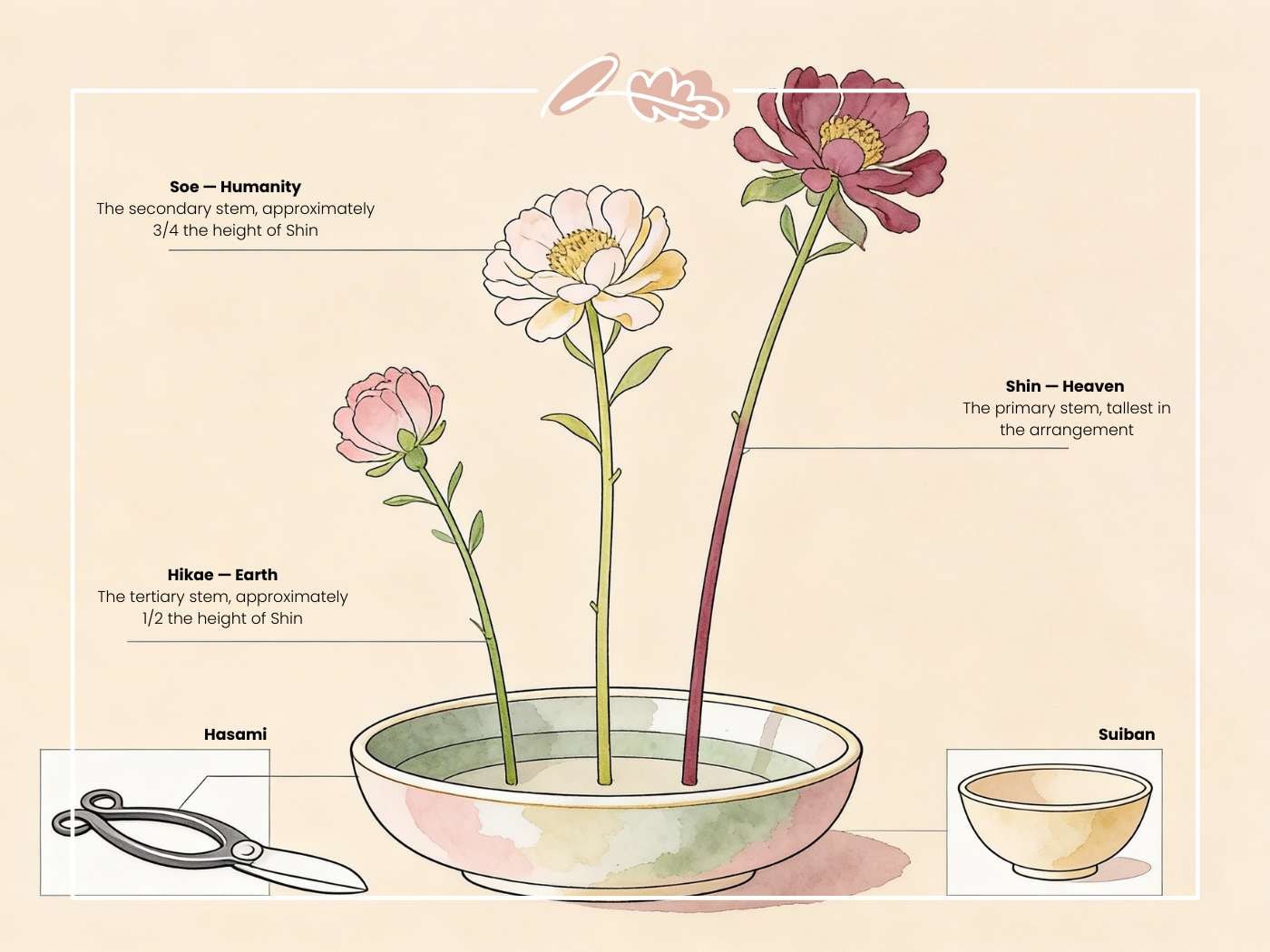

Seika (also called Shoka) functions as a bridge between traditional and modern approaches, establishing the triangular arrangement that represents heaven, human, and earth—the fundamental structure underlying most ikebana arrangements. These three primary stems, called kuge in early terminology, create asymmetrical balance through varying heights and angles.

Moribana, developed by Unshin Ohara in the late 19th century, adapted ikebana for contemporary spaces and Western-influenced living. Using shallow containers and kenzan (pin frogs) rather than tall vases, moribana allows three-dimensional viewing from multiple angles—a departure from traditional arrangements designed for single-perspective tokonoma display.

These two styles address different spatial and aesthetic needs: seika for traditional settings requiring vertical elegance; moribana for modern homes where arrangements may be viewed from various positions. Both demonstrate ikebana’s capacity for evolution while preserving philosophical essence.

Understanding these classic styles prepares practitioners for hands-on practice with materials and techniques.

Essential Techniques and Materials

Building on style knowledge, practical application requires understanding both traditional materials and the fundamental processes that create balanced compositions. Whether working within strict classical parameters or adapting principles for modern ikebana, these technical foundations remain essential.

Traditional Japanese Flowers and Materials

Seasonal awareness guides material selection in authentic Japanese ikebana. Spring calls for cherry blossoms, plum branches, and iris; summer features lotus, morning glory, and bamboo; autumn brings chrysanthemums, maple branches, and pampas grass; winter emphasises pine, camellia, and narcissus.

Beyond flowers, arrangements incorporate branches, leaves, and other natural materials—even dried elements, stones, or moss. This expanded palette distinguishes ikebana from approaches focused solely on blooms. Each material carries symbolic weight: bamboo suggests resilience and flexibility; pine represents longevity; plum blossoms indicate perseverance through hardship.

For practitioners outside Japan, these principles adapt to locally available materials. The key lies not in replicating specific Japanese flowers but in understanding seasonal rhythms, symbolic potential, and the inherent character of chosen materials.

Basic Arrangement Process

The following steps guide creation of simple flower arrangements following ikebana principles:

-

Selecting and preparing vessel: Choose a container appropriate to your style—tall vases for nageire, shallow ceramic bowl for moribana. Consider how the vessel’s shape, colour, and texture will interact with your materials.

-

Choosing seasonal flowers and supporting materials: Gather primary flowers plus branches and foliage, limiting variety to maintain focus. Observe each stem’s natural curve and growth pattern before arranging.

-

Creating the fundamental triangle: Establish the three main positions representing heaven (tallest, typically 1.5–2 times container height), human (medium, two-thirds of heaven’s height), and earth (shortest, one-third of heaven’s height). These branches form your arrangement’s skeleton.

-

Balancing negative space and asymmetrical composition: Position elements to create deliberate emptiness within the arrangement. Avoid symmetry; instead, achieve visual balance through weight distribution across the composition.

-

Final adjustments for harmony and natural flow: Step back, observe from viewing angles, and make subtle adjustments. Remove any element that doesn’t contribute meaningfully—in ikebana, less consistently achieves more.

Comparison with Western Arrangements

Understanding contrasts between approaches helps florists and enthusiasts select appropriate styles for different contexts and clients.

|

Aspect |

Japanese Ikebana |

Western Style |

|---|---|---|

|

Focus |

Lines, space, form |

Flower abundance, colour |

|

Stems |

Highlighted as design element |

Often hidden or minimised |

|

Symmetry |

Asymmetrical balance |

Symmetrical arrangements |

|

Philosophy |

Harmony with nature |

Decorative beauty |

|

Materials |

Branches, leaves, minimal blooms |

Flower-dominant compositions |

|

Space |

Negative space essential |

Fullness preferred |

Neither approach is superior; each serves different aesthetic goals and cultural contexts. A floral artist fluent in both traditions can match client needs precisely—ikebana-influenced arrangements for meditation spaces, minimalist interiors, or clients valuing subtlety; Western abundance for celebrations, romantic occasions, or clients seeking visual impact.

These technical foundations prepare practitioners to address common challenges in practice.

Common Challenges and Solutions

Learning ikebana presents specific difficulties for practitioners trained in other traditions or approaching flower arranging without prior experience. Addressing these challenges directly accelerates skill development.

Achieving Balance Without Symmetry

Western visual training often equates balance with symmetry, making asymmetrical composition feel unstable or incomplete. The solution lies in understanding visual weight distribution: larger blooms carry more weight than delicate stems; darker colours feel heavier than light; horizontal lines suggest stability while vertical lines suggest energy.

Practice by creating arrangements, then photographing them. Review images to identify where visual weight concentrates. Adjust by counterbalancing heavy elements with lighter ones positioned further from centre, much as a seesaw balances unequal weights through positioning.

Creating Meaningful Negative Space

The instinct to fill empty areas undermines ikebana’s essential character. Understanding ma in practical terms means recognising emptiness as active rather than absent—the space between branches is where the viewer’s eye travels and imagination engages.

Avoid overcrowded arrangements by following a simple rule: remove one element more than feels comfortable. If the arrangement still reads clearly, remove another. Stop only when removing anything would break the composition’s coherence. This disciplined reduction develops sensitivity to when space serves the design.

Adapting Traditional Principles for Modern Spaces

Contemporary homes and offices rarely include tokonoma alcoves designed for traditional display. Scaling techniques address this reality: reduce overall dimensions while maintaining proportional relationships; select materials appropriate to smaller spaces; consider viewing angles different from traditional single-perspective display.

Modern ikebana also embraces non-traditional materials—branches from local trees, foraged elements, even sculptural additions—while respecting core philosophy. The Sogetsu School’s principle that “anyone can do ikebana anywhere” liberates practitioners from rigid material requirements while maintaining artistic integrity.

These adaptive approaches ensure ikebana remains a living practice rather than a museum piece.

Conclusion and Next Steps

Japanese flower arrangement offers both meditative practice and practical skill enhancement for anyone working with flowers. Through understanding ikebana’s philosophical foundations, recognising classic styles, and applying fundamental techniques, practitioners develop heightened sensitivity to line, form, space, and seasonal awareness that enriches all floral design work.

To begin incorporating these principles immediately:

-

Create a simple three-stem arrangement using the heaven-human-earth structure, focusing on asymmetrical balance

-

Practice seasonal awareness by noting which materials are currently available in your region and their symbolic associations

-

Study negative space in arrangements you encounter—in shops, homes, photographs—analysing how emptiness contributes to or detracts from compositions

Related topics worth exploring include seasonal flower sourcing strategies, Japanese garden design principles that share ikebana’s aesthetic foundations, and mindfulness practices that enhance creative focus during arrangement work.

Additional Resources

Major Schools and Teaching Approaches

Ikenobo School maintains the oldest continuous lineage, emphasising traditional forms and formal instruction. Ohara School pioneered moribana and welcomes beginners with accessible teaching methods. Sogetsu School embraces creative freedom and contemporary expression. Each offers international chapters and certification programs.

Many foundational texts, manuals, and styles of Japanese flower arrangement began to be documented and standardised during the early Edo period, marking a significant era in the history and development of ikebana.

Seasonal Flower Availability

Looking for a stylish accessory inspired by vibrant blooms? Discover the Bloom and Wild Flower Crown for your next celebration.

Southern Hemisphere practitioners should reverse seasonal associations—cherry blossom season corresponds to early spring in September-October rather than March-April. Local native materials can substitute effectively when traditional Japanese flowers are unavailable, provided symbolic appropriateness is considered.

Traditional Vessel Types and Modern Alternatives

Classic containers include hana-ire (tall vases for nageire), suiban (shallow basins for moribana), and usubata (bronze compote-style vessels for rikka). Modern alternatives include minimalist ceramic bowl designs, clear glass for contemporary spaces, and even found containers that complement material choices. The vessel should support rather than compete with the arrangement.

About This Article — Fabulous Flowers & Gifts

This article was written by the team at Fabulous Flowers and Gifts (fabulousflowers.co.za) — South Africa's trusted luxury florist and gifting destination since 1999. From our studios in Cape Town and Johannesburg, our master florists handcraft every arrangement with heart, care, and over 25 years of expertise. We love sharing what we know about flowers, gifting, and celebrating life's most meaningful moments. Rated 4.8 stars across verified customer reviews.

Explore Our Collections:

Shop Flowers · Flower Bouquets · Flower Arrangements · Gift Boxes · Birthday Flowers · Romantic Flowers · Valentine's Day Gifts · Mother's Day Gifts · Anniversary Gifts · Funeral Flowers · Flowers by Type · Same-Day Delivery · Nationwide Delivery

Weddings, Events & More:

Dreaming of breathtaking wedding flowers? Explore Fabulous Weddings. Planning a corporate function or celebration? Discover Fabulous Events. Curious about who we are and why we do what we do? Read Our Story and find out what makes us different at Our Difference.

Same-day flower delivery in Cape Town & Johannesburg. Nationwide gift box courier delivery across all nine provinces.

About Fabulous Flowers & Gifts:

We're a family-run luxury florist and gifting company based at 18 Toffie Lane, Claremont, Cape Town, 7708 — with additional locations in Sea Point, Cape Town, and South Kensington, Johannesburg. We offer same-day flower delivery in Cape Town and Johannesburg (orders before 12pm, Monday to Saturday) and nationwide gift box courier delivery to all nine provinces — Western Cape, Eastern Cape, Northern Cape, Free State, KwaZulu-Natal, Gauteng, North West, Mpumalanga, and Limpopo — arriving in 2–4 business days.

Tel: +27 21 674 7206 · Email: hello@fabulousflowers.co.za

Meet our little brother brand: Flower Guy — premium-yet-accessible flowers and gifts with a playful twist.